Joseph Marie Jacquard is rarely mentioned in machining textbooks, yet the loom that bears his name represents one of the most important conceptual shifts in the history of manufacturing. Long before numerical control, long before electronics, and even before modern machine tools, the Jacquard loom demonstrated that a machine could execute complex, repeatable operations by following a predefined set of instructions stored outside the machine itself.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, textile production was already partially mechanized, but patterned weaving remained labor-intensive and highly skilled. Creating complex designs required a drawboy to manually lift specific warp threads for each pass of the shuttle. This process was slow, error-prone, and difficult to scale. Jacquard’s innovation, introduced publicly in the early 1800s, replaced this manual decision-making with a sequence of punched cards, each card corresponding to one row of the woven pattern.

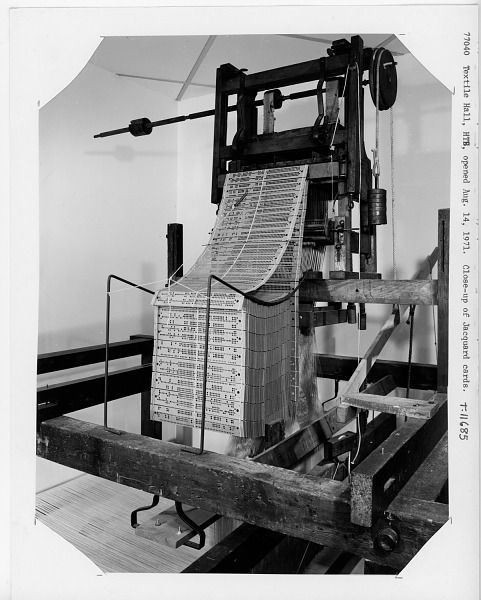

Each punched card contained holes arranged in a rectangular grid. Where a hole existed, a hook passed through and lifted a corresponding warp thread; where material blocked the hook, the thread remained down. By linking cards together into a continuous chain, the loom could reproduce intricate patterns consistently, over long runs, and without continuous human intervention. The loom itself had no understanding of the pattern—it simply followed instructions encoded physically into the cards.

From a modern engineering perspective, this separation is the key idea. The loom’s mechanical structure handled motion and force, while the cards encoded logic and geometry. Changing the design did not require rebuilding the machine; it required changing the instruction set. This distinction between hardware and instructions is fundamental to later developments in automation, numerical control, and computer-controlled manufacturing.

It is important to emphasize that the Jacquard loom was not “programmable” in the modern sense. There was no conditional logic, no feedback, and no ability to modify instructions during operation. The system was entirely open-loop. Nevertheless, it introduced a radical idea: manufacturing outcomes could be controlled by an abstract representation of a process rather than continuous skilled input. In this sense, the loom represents one of the earliest examples of manufacturing knowledge being externalized from the worker and embedded into a system.

The influence of the Jacquard loom extended well beyond textiles. The punched card concept would later appear in mechanical musical instruments, tabulating machines, and early computers. More subtly, it shaped how engineers thought about automation itself. Motion could be guided not just by fixed geometry—cams, linkages, or templates—but by symbolic instructions that could be stored, copied, and reused.

Reference