The idea of the meter emerged during the late 18th century, at a time when France was undergoing the French Revolution and seeking to replace the patchwork of traditional measurement systems with a single, rational, and universal standard. Before this, units of length varied widely from region to region, even within the same country. A “foot” in one city might not match a “foot” in another. The revolutionary government wanted a system based on nature rather than on human anatomy, royal decrees, or local custom. This led to the proposal that the unit of length should be derived from the size of the Earth itself, something that would be the same for all people and all nations.

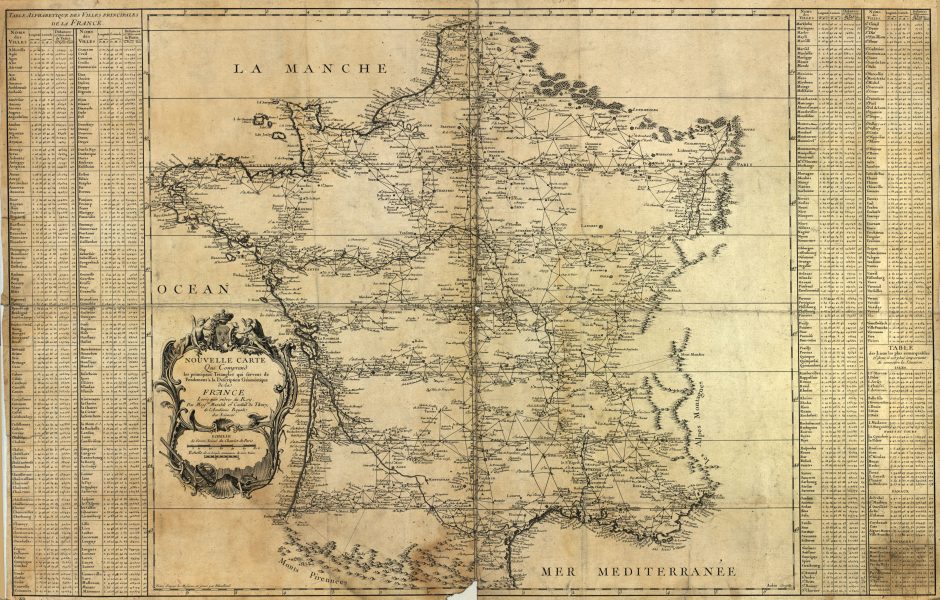

The specific definition chosen for the meter was one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole along a meridian passing through Paris. This made the full distance from the equator to the pole equal to 10,000,000 meters, and the entire circumference of the Earth about 40,000,000 meters. The Paris meridian, a north–south line running through the Paris Observatory, was selected as the reference because France was leading the project and already had a strong tradition of astronomical measurement along that line.

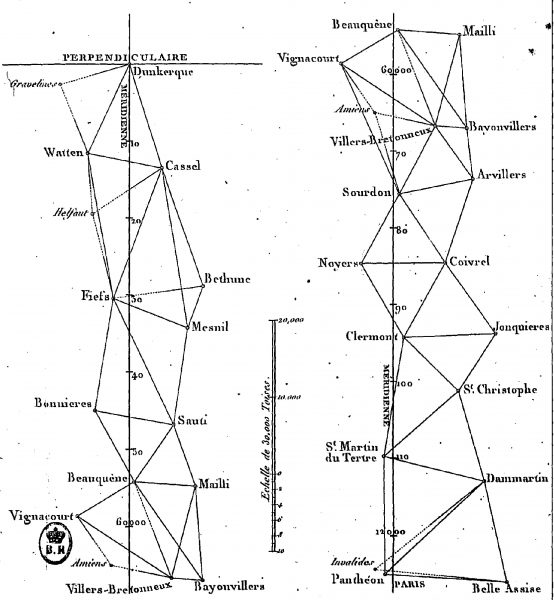

To turn this definition into a usable physical standard, French scientists needed to measure a large section of the Paris meridian as accurately as possible. In 1792, two astronomers, Jean-Baptiste Delambre and Pierre Méchain, were tasked with surveying the arc of the meridian from Dunkirk in the north to Barcelona in the south. This distance covered roughly ten degrees of latitude and crossed difficult terrain, including rivers, mountains, and politically unstable regions during a time of war and revolution.

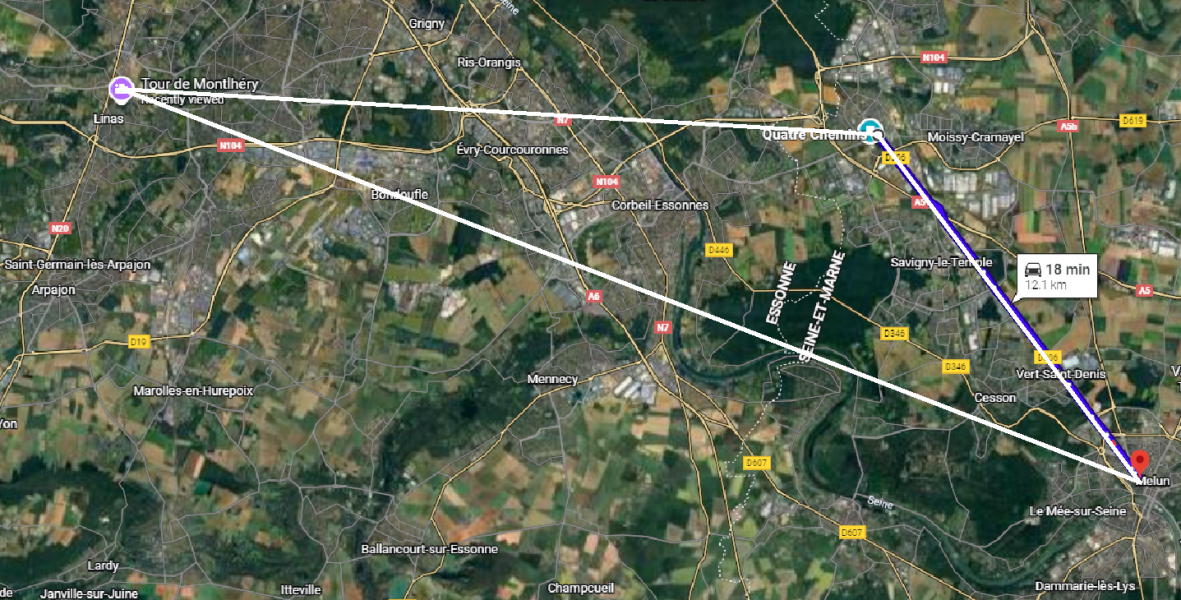

The geodetic survey that led to the definition of the meter began with the careful establishment of a measured baseline between two fixed reference points near Lieusaint and Melun, each marked by a small pyramid-shaped monument known as termes. These pyramidions were not symbolic decorations but practical geodetic markers: they identified the exact endpoints of the baseline with permanent, visible precision. Along the straight road between them, Delambre’s team measured the distance using calibrated metal rods laid end-to-end, applying corrections for temperature and alignment. Once this baseline length was fixed, the pyramid markers served as the foundational stations from which angles were measured to distant towers (like the Tour de Montlhéry) and hilltop signals, allowing the triangulation network to expand north toward Dunkirk and south toward Barcelona. In this way, the entire continental survey — and ultimately the meter itself — was anchored to two small pyramids set into the French countryside.

The method they used was triangulation. Instead of measuring long distances directly on the ground, which would have been impractical and inaccurate, they measured angles between carefully selected points such as church towers, hilltops, and signal stations. By measuring one baseline distance very precisely and then using geometry, they could calculate the distances between many other points. This network of triangles allowed them to determine the length of the meridian arc with remarkable precision for the time.

The survey took several years and was filled with challenges. Méchain, working in the southern section, became troubled by small discrepancies in his astronomical measurements near Barcelona. He believed he had made errors and spent years trying to correct them, even though the differences were extremely small. Delambre, covering the northern section, faced suspicion from local populations who often mistook his instruments for military or espionage equipment. Despite these difficulties, the data were eventually compiled and used to calculate the length of the meter.

In 1799, a platinum bar representing the meter was produced and deposited in the French National Archives. This bar became the first physical realization of the meter, known as the “mètre des archives.” Although later analysis showed that the original Earth-based measurement was slightly off due to limitations in geodesy and the Earth’s irregular shape, the meter itself became a stable and widely adopted standard. The exact value mattered less than the fact that everyone now agreed on the same unit.

After the original meter was established in 1799 as a platinum bar based on the Paris meridian survey, it quickly became clear that relying on a single physical object had limitations. The bar could be damaged, contaminated, or subtly altered over time, and it existed in only one place. As science and engineering advanced in the 19th century, the demand for greater precision and reproducibility grew, especially in fields such as surveying, astronomy, optics, and precision manufacturing. This led to the idea that the meter should be defined not by a physical artifact, but by a natural phenomenon that could be reproduced anywhere in the world.

In 1889, a new international prototype meter was adopted, made from a platinum–iridium alloy and stored near Paris. This bar was more stable than the original, and identical copies were distributed to other countries. Even so, it was still an artifact-based standard. Scientists began looking for ways to define length using light, since light waves have extremely regular and measurable properties. By the early 20th century, advances in spectroscopy made it possible to measure wavelengths of specific colors of light with very high precision.

In 1960, the meter was officially redefined in terms of light for the first time. Instead of a metal bar, the meter became a specific number of wavelengths of light emitted by krypton-86 atoms. The definition stated that one meter was equal to 1,650,763.73 wavelengths of the orange-red radiation corresponding to a particular electronic transition in krypton-86. This was a major shift. Length was now tied to atomic behavior rather than to a physical object or a geodetic measurement of the Earth. Laboratories around the world could reproduce the meter by using krypton lamps and optical interferometry, greatly improving consistency and precision.

As laser technology matured in the 1960s and 1970s, scientists gained the ability to measure both time and frequency with extraordinary accuracy. This made it possible to link length even more directly to the speed of light, which had been measured with increasing precision and was found to be remarkably constant in vacuum. Since speed is distance divided by time, and time could already be measured extremely accurately using atomic clocks, it made sense to define length in terms of time and the speed of light.

In 1983, the meter was redefined once again, this time in its modern form. The new definition stated that the meter is the distance light travels in vacuum in 1/299,792,458 of a second. Instead of measuring wavelengths directly, scientists now fixed the value of the speed of light and used precise time measurements to determine length. This tied the unit of length to two fundamental constants: the speed of light and the second, which is defined using the oscillations of cesium-133 atoms.

This evolution reflects a broader shift in metrology, the science of measurement, away from physical artifacts and toward definitions based on invariant properties of nature. The original Earth-based definition of the meter was revolutionary because it sought a universal standard rooted in the size of the planet itself. The later wavelength-based definition improved precision by using atomic physics. The current light-speed definition goes even further by grounding length in fundamental constants that are believed to be the same everywhere in the universe.

Despite these changes, the conceptual role of the meter has remained the same. It is still the fundamental unit for describing length, distance, and spatial extent. What has changed is the method by which that unit is realized. The Paris meridian survey represents the meter’s origin in Enlightenment-era geodesy and geometry. The wavelength definition represents the rise of atomic physics and spectroscopy. The speed-of-light definition reflects modern physics and precision timekeeping. Together, they tell a story of how our ability to measure space has become steadily more precise, more universal, and more deeply connected to the fundamental laws of nature.

The Paris meridian survey remains historically important because it represents one of the earliest attempts to base a unit of measurement on natural, global phenomena rather than on local tradition. It also marks the beginning of the metric system as a scientifically grounded, internationally oriented framework. In many ways, the meter’s origin reflects the broader Enlightenment goal of replacing arbitrary standards with rational, universal ones grounded in observation, geometry, and physics.